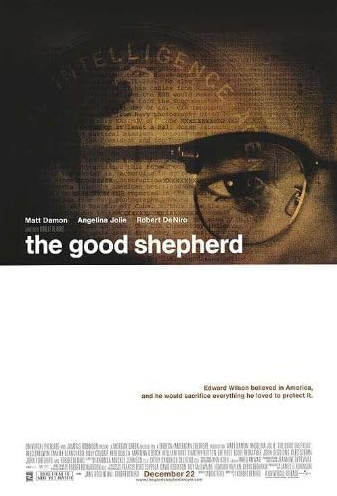

The Good Shepherd, Robert De Niro’s second film under his direction, claims to relate the tale of the formation of the CIA during the height of the Cold War. The film is a powerful yet patience-demanding production that will have some spectators sitting up in riveting fascination while others wriggle restlessly in their seats. It is loosely based on the lives of two intelligence operatives, James Jesus Angleton and Richard M. Bissell Jr. The Good Shepherd relies on ambiance and dialogue, as well as the patient goodwill of its viewers, to convey its message. At 168 minutes long and with little actual action to speak of, “The Good Shepherd” is admittedly not the easiest sell for a large audience.

Played by Matt Damon, Edward Bell Wilson is a skilled counterintelligence agent. The Bay of Pigs disaster in the spring of 1961 and the theory that an agency mole must have informed the Cubans of the American government’s invasion plan serve as the film’s framing devices. The film covers Edward’s life as it shifts between the 1940s and the 1960s, contrasting his early ardent loyalty with the paranoid, lonely, and resentful man he becomes later in life. “The Good Shepherd” is a concise examination of a guy who understands the importance of family, love, friendship, and parenting but substitutes them for patriotism and duty.

Wilson is a man who, in many respects, is the perfect fit for the life of dedication and solitude that espionage work, by its very nature demands, and is almost entirely devoid of humour and emotions. He hardly smiles once throughout the narrative, and he spends so much time at work that he doesn’t see his wife or small kid for extended periods of time. Wilson is undoubtedly one of the least likeable movie heroes in recent memory, or at least he would be if Damon hadn’t successfully portrayed the kind of puppy fragility that makes us care about the character. Even though we are aware that he has dedicated his life to a cause he believes to be good and honourable, we find it difficult to support the way he treats his wife and family. However, Damon is able to demonstrate to us that Wilson is not overly pleased with himself either and that he would live a different life if only he could escape his own skin and begin again. However, he is unable to achieve this, so he is stuck with his fate. He stays faithful to what he is capable of doing and hopes that the gods may grant him some forgiveness in the end. Damon never gives us more information about the character than we absolutely need to know since he keeps his cards so close to his chest. Wilson may occasionally be evaluating his life, but the filmmakers don’t feel the need to outright give us all the specifics. The real drama is in what’s going on behind those spectacled eyes.

De Niro has chosen to concentrate on the characters and conversation and simply hope that his audience would follow along with him in his film rather than making it for the action crowd. As a director, he gives the narrative a calm, sombre tone to better reflect the demeanour of his lead character. Cinematographer Robert Richardson employs a flat colour scheme for the scenes set in the present and a warm, sepia-toned look for those set in the past to create a sense of contrasted emotions.

De Niro excels at meticulously, almost microscopically dissecting Edward’s existence as an intelligence officer. This man’s entire soul is exposed for everybody to see. It enables the viewer to appreciate him while yet feeling sorry for him. It is arguably the best espionage exploration in film history. The fundamental essence of this character is known to us.

Take a look at the numerous great scenes in which the CIA lab experts methodically examine a grainy black-and-white photo and a subpar audio clip. It is an intricate study that functions as a microcosm for the entire film. It is clear that De Niro’s famous commitment to character detail has carried over to his filmmaking. Everything worthwhile in “The Good Shepherd” is found in the small details—the fleeting glances, the awkward silences, the verbal cues and hints.

The Good Shepherd is not a spy movie, but rather a depiction of a guy who is slowly following in his father’s footsteps. He never permitted himself to live for himself while serving his country. While America was able to prosper, his own enjoyment of life was stunted, and he was left with no choice but to watch all that was positive about it gradually pass into history.